VOL. I

Case Study

From Fireflies to Fiber Optics: How Netflix Streams Your Favourite Shows

Written by

Ayushman

9th Apr, 202523 min read

Written by

Ayushman

I didn't expect a viral trend of AI-generated Studio Ghibli art to lead me back to Grave of the Fireflies. Yet there I was, a bowl of ice cream in hand, streaming this 1988 masterpiece on a quiet evening. The internet had been flooded with whimsical AI images of Ghibli characters, and it sparked a wave of nostalgia strong enough to hit play on the real thing. As the opening scene rolled in, I settled in — and so did Netflix, ready to deliver an uninterrupted viewing experience. No buffering, no dips in quality — just smooth, high-quality streaming from start to finish.

It got me thinking: how does Netflix manage to serve up flawless playback, even when millions of people are binging their favourite classics at the same time? In this deep dive, we'll explore the tech magic behind it — from adaptive streaming and smart video codecs to edge caching and content delivery networks. We'll keep it light, clear, and a little playful, with nods to that Ghibli night as we unravel what keeps our screens smooth and our stories flowing.

The moment I clicked Play on Grave of the Fireflies, Netflix’s player sprang into action to deliver the video. But unlike a simple file download, streaming a movie involves a clever trick: Adaptive Bitrate Streaming (ABR). Ever noticed how sometimes a video starts a bit blurry and then becomes sharp, or seamlessly drops to lower quality when your Wi-Fi falters? That’s ABR at work, dynamically adjusting video quality to match your internet speed in real time. Netflix wants playback to start instantly and never stall unexpectedly, even if your network conditions change.

Netflix encodes each movie or show in multiple quality levels (from low-res, low-bitrate up to high-res, high-bitrate). The video is chopped into small pieces (usually a few seconds each). When you start watching, the Netflix client (the app on your TV, phone, browser, etc.) quickly grabs an initial chunk at a lower quality to start playback fast. As it plays, the client measures your bandwidth and possibly your device’s capacity, then switches to higher or lower bitrates for subsequent chunks depending on what your connection can handle . If your internet is fast, Netflix ramps up to a high bitrate (crispy HD or 4K goodness); if your connection slows (say someone else in the house starts a download), the app gracefully steps down to a lower resolution stream to avoid buffering. All of this happens adaptively, on the fly, without you lifting a finger.

It’s like Netflix is constantly tuning an antenna for the best signal – but digitally. The moment I hit play on that Ghibli film, the app initially didn’t know my Wi-Fi could handle HD, so it likely started with a modest bitrate. Within seconds, seeing that my network was stable and fast, it would’ve cranked up to a higher quality stream. I barely noticed any change except that those beautifully animated scenes quickly sharpened to their full glory.

How does the Netflix app decide what quality to pick? It uses an ABR algorithm – essentially some smart rules. Different streaming services use different approaches. Some algorithms are throughput-based (they look at recent download speed: if the last chunk downloaded super fast, maybe increase quality). Others are buffer-based (they look at how much video is already buffered in the app: if there’s a healthy cushion, maybe we can afford higher quality).

Netflix has experimented with hybrid approaches that use both throughput and buffer occupancy to make decisions. In fact, research done with Netflix data showed that focusing on buffer size can reduce rebuffering (those dreaded pauses) by 10–20% compared to naive algorithms. The Netflix player aims to keep you in a sweet spot: high enough quality for your screen, but not so high that you’ll run out of buffered video if your connection hiccups.

Netflix doesn’t stream video as one continuous blob; it sends those small chunks using standard web protocols. The two main formats in the streaming world are DASH (Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP) and HLS (HTTP Live Streaming). Think of these as two dialects of the same language – both speak in terms of manifests and segments, but with a slightly different accent.

MPEG-DASH is an international standard for adaptive streaming that Netflix (and many others) have embraced. It works by breaking content into segments (just like we discussed) and providing a manifest file (often with extension .mpd) that lists the URLs of all those segments for each quality level. When you hit play, the Netflix client fetches the manifest, which essentially says: This video is available in, say, 10 different bitrates; here are the segment files (timestamps 0-4 seconds, 4-8s, etc.) for each version. The client will then start grabbing segments one by one from one of those versions, switching up or down as needed. DASH is codec-agnostic and very flexible – it doesn’t care if the video inside segments is encoded with H.264, H.265, VP9, or whatever.

Major streaming platforms like YouTube, Hulu, and Netflix rely on MPEG-DASH to deliver high-quality experiences to viewers.

Following is an example .mpd file.

HLS, on the other hand, is Apple’s proprietary take. It works similarly but uses .m3u8 playlists and, until recently, was limited to Apple-approved codecs like H.264 and HEVC. Apple devices—iPhones, iPads, Apple TVs—require HLS, which has long been a thorn for streamers who want a unified delivery system. Want to use the more efficient AV1 codec on Safari? Good luck. Apple’s strict HLS preference has slowed broader adoption of newer, better codecs on their platforms.

Netflix navigates this by simply using HLS for Apple devices and DASH for everything else. It’s like having two roadmaps for the same destination. Under the hood, you won’t notice—whether it’s DASH or HLS, your stream arrives chunk by chunk, adapting quality on the fly.

And thanks to both formats riding on good old HTTP, those segments play nicely with web infrastructure like firewalls and CDNs. Which raises the next question: how does Netflix get these video chunks to you so fast? Before we dive into the network side of things, let’s talk about the unsung hero that keeps everything running smoothly—buffering.

As I watched Grave of the Fireflies, one thing I thankfully didn’t experience was the dreaded buffering wheel. Netflix works extremely hard to avoid those interruptions. The key to that smooth experience is how the Netflix player manages its buffer.

The buffer is just a chunk of memory (or storage) where the streaming app accumulates video data ahead of what you’re currently watching. For example, if you’re 5 minutes into the movie, the app might have already downloaded up to minute 7 or 8 and has those minutes waiting in the buffer. That way, even if your internet blips out for a moment, playback can continue using the buffered data. The larger the buffer (in seconds), the more resilience against network hiccups. But buffers can’t be too large (devices have finite memory, and huge buffers could introduce long delays before playback starts). Netflix strikes a balance with smart buffering strategies.

When you hit play, there’s an initial startup buffer that the player tries to fill before the video starts. You may notice Netflix usually begins playing very quickly (often within a couple of seconds or less). They likely start with a small buffer (maybe a few seconds of video) to minimize startup delay, possibly using a lower-quality segment to fill those seconds faster. Once the video is rolling, the player continues to buffer ahead in the background – constantly downloading the next chunk(s) of the movie. Netflix wants to keep that buffer sufficiently filled at all times. If it ever runs out (i.e., the video catches up to what’s been downloaded and nothing new has arrived), that’s when you get a buffering stall.

How does the player ensure a healthy buffer? It’s partly by choosing the right bitrate (ABR logic) and partly by reacting to buffer levels. For instance, Netflix’s ABR algorithm might be coded to be more conservative if the buffer starts getting low – e.g. if it only has, say, 10 seconds of video buffered (maybe due to a momentary slow network), the algorithm might temporarily drop to a lower bitrate stream to download future segments faster and refill the buffer. Conversely, if the buffer is comfortably, say, 30 seconds full, the player might risk downloading a higher quality chunk next. Some adaptive algorithms are explicitly buffer-based: they decide quality directly based on buffer occupancy. In fact, a study co-authored by Netflix engineers found that a simple buffer-occupancy rule (with a bit of throughput logic at start) could reduce rebuffers notably. So modern streaming players, including Netflix’s, often use a hybrid approach: use recent throughput to guide initial and rapid changes, but use buffer level to fine-tune steady-state behavior.

Buffering isn’t just about avoiding pauses; it’s also about smooth quality shifts. If Netflix needs to drop your video quality, it prefers to do it before you run out of video (to avoid a pause). By downloading a lower-bitrate segment ahead of time, you might notice a dip in resolution for a while, but the video keeps playing. Which is the lesser evil? A brief quality drop is usually far less annoying than an outright pause in playback. Netflix knows that a single rebuffering event (that dreaded pause) can really hurt user satisfaction. (Industry research has shown viewers will abandon a stream or get frustrated if buffering happens often). So the adaptive logic always errs on the side of no pause, even if it means fluctuating the quality.

Netflix themselves put it plainly: they want playback to start on cue and never stop unexpectedly . Achieving that is a complex dance of the ABR algorithm and buffering strategy. We’ve covered how the client picks video quality and buffers it – but what about the video data itself? We’ve been tossing around terms like bitrate, quality, resolution… Let’s dig into the actual video compression that makes streaming possible at all.

A codec’s job is to compress raw video into manageable chunks of data. Without compression, a movie like Grave of the Fireflies (which is about 90 minutes of hand-drawn gorgeousness) would be hundreds of gigabytes in raw form – impossible to stream over a typical internet connection. Codecs reduce that size dramatically by encoding video in clever ways, trading off some quality for a huge reduction in data. Netflix has been a leader in adopting modern codecs to deliver higher quality at lower bitrates.

Let’s introduce the main video codecs you’ll encounter with Netflix:

H.264. It offers decent compression and is widely supported by hardware (every phone, PC, smart TV can decode H.264). However, it’s showing its age – newer codecs can achieve the same quality with much less data. Netflix still provides H.264 streams for compatibility (and for lower tiers like 480p/720p on some devices), but for HD and beyond they’ve largely moved to more efficient codecs.H.264, HEVC can deliver similar quality at about 50% less bitrate. Netflix uses HEVC especially for 4K Ultra HD content and HDR content – those massive high-res streams simply need better compression. If you watch Netflix on a 4K TV, you’re likely getting an HEVC stream (assuming your device supports it and you have the Ultra HD plan). Apple devices also prefer HEVC for high resolutions. The downside of HEVC is it’s patent-encumbered (i.e., companies have to pay licensing fees to use it), which motivated Netflix and others to explore royalty-free alternatives.VP9 is a codec offering efficiency on par with HEVC in many cases, and it’s royalty-free. Netflix started adopting VP9 especially for streaming to devices that support it, like Android phones, Chromecast/Android TV, and even in Chrome browsers. If you watched Netflix on an Android phone in recent years, you were likely benefiting from VP9’s compression (saving your data plan some bytes). VP9 typically gave about 30%+ bitrate savings over H.264 at the same quality. Netflix wouldn’t necessarily use VP9 on devices that already handle HEVC (like many Smart TVs) – often it’s one or the other. But having VP9 allowed Netflix to serve high-quality video without relying solely on HEVC’s licensed tech.AV1 is a cutting-edge, royalty-free codec developed by the Alliance for Open Media (Netflix is a founding member of that alliance). It provides about 20-30% better compression than VP9/HEVC for the same quality – meaning even smaller files and lower bitrates for equal (or even better) picture fidelity. Netflix began streaming AV1 on Android in 2020, using software decoding (thanks to an efficient decoder called dav1d). Under poor network conditions, AV1 really shines – Netflix reported improved experience on flaky connections using AV1. More recently (as of 2021-2022), AV1 support has spread to TVs and consoles; Netflix has started streaming AV1 to supported Smart TVs as well. If your TV or device has an AV1 decoder (many newer models do), Netflix might deliver AV1 for an even more bandwidth-friendly stream. The result: higher quality per bit, and more resilience on slow connections. For example, those delicate watercolor backgrounds in Grave of the Fireflies could maintain their detail even if my bandwidth was limited, because AV1 squeezes more out of each kilobyte.Netflix chooses which codec to use based on the device capabilities and the content. They also do something really clever: per-title encoding optimizations. Instead of one-size-fits-all settings, Netflix analyzes each movie/episode and decides the best bitrate ladder for it. Action-heavy content might need higher bitrates for 1080p than a static talking-head documentary. Animation (like Ghibli films) can sometimes be encoded at lower bitrates for the same quality because of simpler backgrounds or fewer chaotic motion patterns. Netflix’s encoding team actually determines optimal resolutions/bitrate steps for each title individually, so that no bits are wasted. The goal is to use the minimal bandwidth while still giving a great picture for that specific title.

Here’s a fun fact: It’s been said that Netflix generates around 1,200 different encoded files for a single movie 😲 to cover all the combinations of codecs, resolutions, audio, subtitles, etc., across their 2200+ supported devices. That’s a staggering number of versions! (Imagine each movie exists in 1,200 forms on Netflix’s servers – from a low-res mobile stream to a 4K HDR stream in various codecs, plus audio tracks in dozens of languages, subtitles, etc.) This multi-version approach is what enables that adaptive streaming: whatever your device and connection, Netflix likely has a version that’s just right for it.

In my Grave of the Fireflies session, Netflix likely served me an AV1 or VP9 stream (since I was using a modern setup) at 1080p. The quality was breathtaking – not a compression artifact in sight, every frame of firefly glow pristine. And yet, the data usage was optimized. I didn’t think about it at the time (I was too busy thinking about the fate of the characters), but the reason those visuals looked so good is decades of codec evolution and Netflix’s meticulous encoding. The bottom line for viewers: more efficient codecs mean better video with fewer bits, which especially matters if you have bandwidth caps or if you’re watching on a slower connection. It’s also crucial for emerging markets where internet speeds may be lower – Netflix can reach those audiences by using advanced codecs to stream video on thinner pipes.

Now, having all these versions of video is one thing – getting them to you efficiently is another. When I pressed play, where exactly was the video coming from? You might assume from Netflix’s servers somewhere in the cloud. True, but Netflix’s cloud is a bit unique. It’s not just sitting in one data center – it’s distributed across the globe in what they call Open Connect. Let’s dive into how Netflix pushes all these video bits through the internet so reliably, even when a sudden Ghibli art trend causes thousands of people to stream Grave of the Fireflies at once (not saying I started a trend, but who knows!).

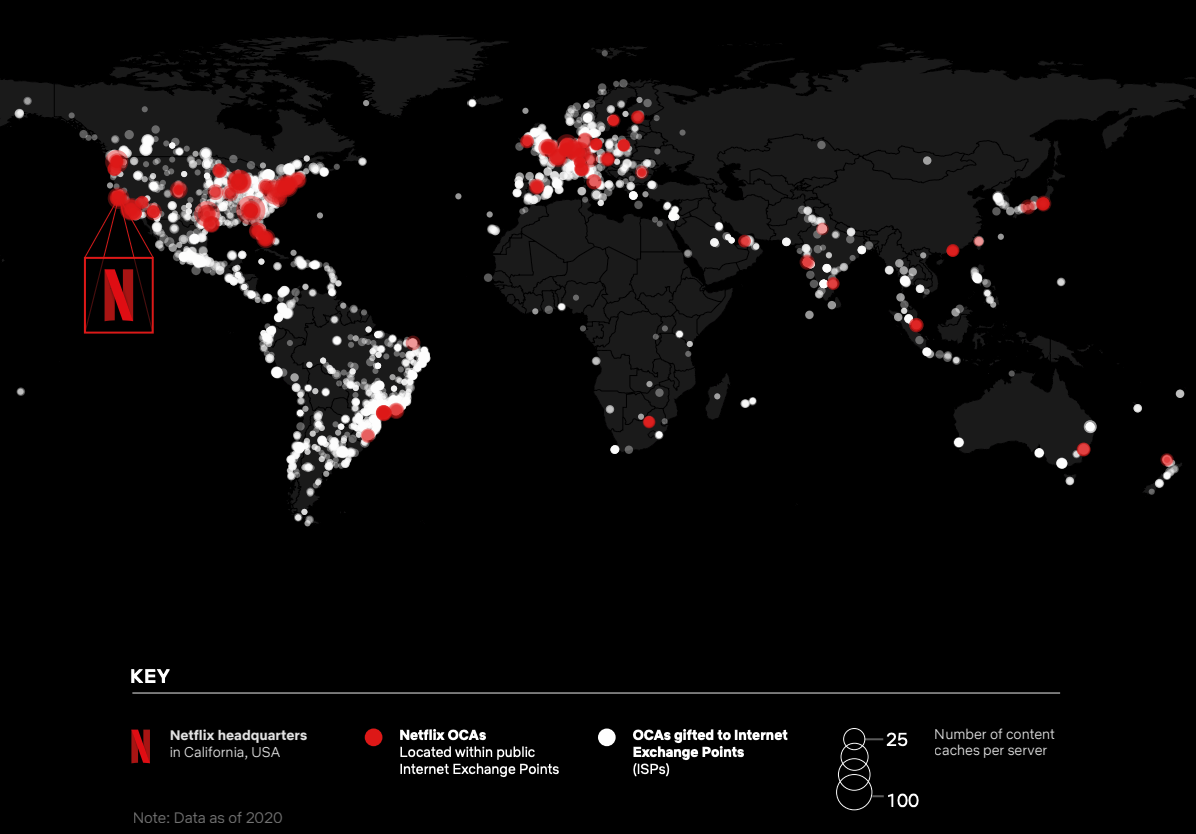

When you stream on Netflix, the video data isn’t usually coming from some far-off central server. Instead, it’s likely coming from a server near you, possibly even within your internet service provider’s network. This is thanks to Netflix Open Connect, the company’s private Content Delivery Network (CDN). Netflix delivers a whopping 95% of its data traffic through direct connections via Open Connect appliances in ISPs. In plain terms: Netflix strategically places caching servers all over the world so that your movies and shows don’t have to travel far.

Here’s how it works: Netflix provides special server boxes called Open Connect Appliances (OCAs) to ISPs (Internet Service Providers) for free. These are basically high-powered caches loaded up with Netflix content. If your ISP participates (and over a thousand ISPs do worldwide), they might have a Netflix OCA in their data center right in your city or region. Popular Netflix content (especially new releases, popular series, regional favourites) is stored on these local servers. So when you hit play, the Netflix backend (running in AWS cloud) will route your streaming request to the nearest OCA that has the content. Rather than your stream coming across the globe, it might just come from down the street!

In my case, streaming Grave of the Fireflies from my home in the evening, Netflix likely directed my video segments from an Open Connect server my ISP hosts in the metro area. Even though it’s an older film, the trend of AI Ghibli art could have caused many viewers in my region to watch it around the same time. Netflix’s system (via a steering service) would choose an OCA that had Grave of the Fireflies already cached. If by chance it wasn’t cached locally (maybe it wasn’t super popular in my region until then), Netflix’s system might pull it from a regional hub or an Internet Exchange where they have servers (Netflix also deploys OCAs at internet exchange points for broader coverage). But once one person in an area requests a movie, that local OCA can cache it so the next person gets it locally. It’s like Netflix has built thousands of mini-Blockbusters inside ISP networks, stocked with the most-requested titles.

Why does this matter? Because it dramatically reduces latency and potential congestion. If 10,000 people in one city all decide to stream Squid Game at 8pm, Netflix’s architecture ensures that those streams are served from nearby caches rather than each coming all the way from a central server cluster. The data travels over short ISP-internal routes, not over long-haul links. This eases the load on internet backbones and reduces points of failure. The result: faster start times and less chance of quality drops due to network issues in between. It’s a big part of how Netflix can maintain video quality even during peak hours. (It’s also how Netflix handles sudden surges when new episodes drop or, say, when a random 35-year-old anime film suddenly becomes trending – the CDN absorbs the wave by delivering from the edges). Netflix Open Connect is often cited as a competitive edge).

They’ve essentially taken on the work of content distribution themselves rather than relying purely on third-party CDNs. Those red Netflix server boxes are scattered across 233+ locations in over 6 continents by some counts. They even tailor which content to pre-load in each server based on regional viewing habits. (I wouldn’t be surprised if an OCA in Japan has every Ghibli film cached 24/7, whereas one in another region might load them on-demand if interest spikes.)

Let’s paint the picture of what happened network-wise when I played that movie: My Netflix app communicated to Netflix’s cloud control (running in AWS) – User wants to watch Grave of the Fireflies. Netflix’s backend (Play API, etc.) verified I have permission (subscription ok, the title is available in my region, etc.). Then, it consulted a Cache Control Service that knows which OCAs have what content and the health of those caches. A Steering Service (Netflix codenames parts of this system as CODA for the decision logic, etc.) picks the best server for me – usually the closest one with the content available and with capacity. It returns to my device a set of URLs that point to that local OCA for the video segments. From that moment on, my device is fetching the chunks directly from the OCA via HTTP. The Netflix cloud services in AWS aren’t streaming the video themselves; they just orchestrated the handoff. This is a lot like a traffic control system: once I’m handed off to the local road (OCA), I get off the highway (Netflix’s central servers).

If that local OCA goes down or can’t serve for some reason, Netflix can failover seamlessly – it might pick another nearby OCA or fall back to an internet exchange server, or in worst case, even pull from an AWS datacenter. They have routing logic for these scenarios. But those are fallbacks; normally, it’s all local.

This distributed caching system not only improves performance but also saves Netflix a ton on bandwidth bills (serving locally via peering with ISPs is cheaper than pumping all data from AWS across the internet). It’s a win-win: users get smoother streams; Netflix (and ISPs) reduce costly network transit. In fact, ISPs generally love having OCAs because it offloads traffic that would otherwise traverse their upstream links.

Now, up until now we’ve focused on delivering the current video you’re watching. Netflix, however, is always thinking one step ahead. Have you noticed how after one episode finishes, the next one often starts almost instantly? Or how scrolling through Netflix’s home screen feels snappy with previews ready to play? That’s not telepathy – it’s prefetching. Let’s see how Netflix tries to stay ahead of your next move, pre-loading data to make your experience seamless.

Toward the end of Grave of the Fireflies, Netflix was likely already preparing something else for me: perhaps the next piece of content to show. Indeed, one way Netflix keeps things smooth is by prefetching data that you’re likely to request next. This could be the next episode in a series, details for a title you might click on, or even just the next few seconds of video while you’re watching.

We already talked about how the Netflix player buffers ahead within a video (that’s a form of prefetching: downloading the upcoming segments before you watch them). But Netflix goes further: it also prefetches future content based on predictions. Let’s break down a few key prefetching techniques Netflix employs:

All these prefetching behaviors have to be tuned carefully. Netflix doesn’t want to waste bandwidth sending you stuff you never watch. So the predictions have to be reasonable (e.g., it probably won’t prefetch an entire movie just because you browsed to its detail page, unless it’s very confident you’ll hit play). But certain things have high probability – next episodes in a binge, the first few seconds of whatever auto-plays on the home screen, etc. Those are worth the small bandwidth cost to avoid any user-visible delay.

In my anecdotal case: after finishing the emotionally draining film, Netflix suggested a light-hearted Ghibli movie (My Neighbor Totoro, a common recommendation to cleanse the palate). I didn’t end up watching it that night, but had I clicked it, I suspect it would have started very fast. Possibly Netflix had already fetched the opening scene of Totoro when it popped up that recommendation panel, expecting a sorrowful viewer like me might need a comforting follow-up immediately. The app could do this because it knows what content is being recommended next and has the idle network capacity while I’m still deciding or watching credits.

Prefetching also occurs at the network edge: those Open Connect caches we talked about can pre-load popular new content proactively (for instance, at 3am before a big show release, so the episodes are on every local server by morning). That way the data is already local before anyone even requests it. The cache then might even serve prefetch requests quickly if multiple people start watching around the same time.

All these tricks contribute to Netflix’s it just works feel. You rarely click something and wait – it’s either instant or very close to it. And that’s intentional. In a world where entertainment is a click away, any friction could turn off a viewer. Netflix’s prefetching ensures that from browsing to playing to binge-watching, everything feels smooth and responsive.

"Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

- Arthur C. Clarke

These days, I find myself drawn to what lies beneath the surface — the gears behind the curtain, the systems behind the screen. We live in a world where so many things just work, and we often don’t stop to ask why or how. But the more I’ve started exploring these everyday miracles, the more I’ve come to appreciate the astonishing effort it takes to make something feel effortless.

Take Netflix, for instance. A single click of the Play button sets off a cascade of engineering brilliance: encoding pipelines tuned for perceptual quality, edge caches deployed around the globe, resilient failover systems, real-time adaptive algorithms, and predictive prefetching mechanisms — all choreographed in milliseconds. And yet, the user experiences none of this complexity. They simply watch. That’s the magic.

"The highest form of engineering is making complexity invisible.

And then there’s Ghibli.

I grew up watching Studio Ghibli films. They weren’t just movies — they were windows into quieter worlds, where magic wasn’t loud, but gentle. Where characters found peace in the small, still moments. Where the wind in the trees or the soft clatter of dishes said more than dialogue ever could. Those films shaped the way I see stories — and maybe even the way I see life. If you’ve never watched one, I sincerely hope you do. In a world that often feels chaotic, Ghibli’s worlds offer something rare: calm.

"The more you leave out, the more you highlight what you leave in.

- Henry Green

Netflix’s tech fades into the background, not because it’s simple — but because it’s designed to disappear. Like the studio stage crew that dims the lights, opens the curtain, and sets the scene — their work is most successful when it isn’t noticed. But for those of us who peek behind the curtain, it’s nothing short of a masterpiece.

So the next time you binge a series, or rewatch an old favourite, or even explore a Ghibli movie for the very first time, take a second to marvel — not just at the story you’re watching, but at the quiet brilliance that delivers it to you. From fiber optics and frame buffering to machine learning and chaos engineering — this isn’t just entertainment. It’s a symphony of engineering, crafted with care so that all you have to do is sit back and feel something.

And honestly, isn’t that beautiful?

"The mark of great design isn't loud brilliance — it's the kind that makes you feel, without ever needing to explain how.

Thank you for reading. And if you’re looking for something to watch next, I gently recommend My Neighbor Totoro . It’s a warm hug of a film — quiet, magical, and full of the kind of softness this world could use a little more of.